“Human Action” and Robert Murphy’s “Choice,” Part 4: Rounding Out the Basics

This is Part 4 of my ongoing series of posts summarizing Bob Murphy’s indispensable book Choice: Cooperation, Enterprise, and Human Action. Murphy’s book is itself is a summary of Ludwig von Mises’s classic treatise “Human Action” — so you’re reading a summary of a summary . . . which sounds about right for a blog post, no?

The idea of this series of posts is to popularize and spread the word about Austrian economics and educate the public. I have created a category for all these posts, called “Human Action and Choice,” so that all these posts can be read (in reverse order) with a single click. Note well: any errors in these summaries are mine and not Murphy’s.

In this post, we will be defining some terms, which is an exercise that is critical to any future discussion. We will also learn a concept that separates Austrian economics from classical economics: the heterogeneity of capital. Unlike classical economists, Austrians do not view capital as one large lump. They see the capital structure as composed of different types of capital, some geared towards longer-term goals than others. As we will see later, this more accurate view of capital has staggering implications for the business cycle. Based on my reading, it seems to me that this concept is utterly foreign to classical economics, and allows Austrians to better understand the effect of changes in the monetary supply and interest rates.

In keeping with the Austrian desire to explicate universally applicable concepts, we simplify everything to a desert island, with a hypothetical Robinson Crusoe, trying to manage his environment. This sort of approach drives the Paul Krugmans of the world crazy, but it helps illustrate universal concepts that apply to any human actor.

The key insight is to classify goods as “lower-order” or “higher-order” based on how close they are in the production process to satisfying a consumer’s desire. Lower-order goods are the closest to satisfying a desire. In particular, consumer goods are goods that directly satisfy a desire. For example, Robinson Crusoe is hungry, and eats a coconut sitting on the ground. The coconut is a consumer good, or “first-order” good, because it directly satisfies Crusoe’s needs. It is the lowest-order good possible.

Goods used to produce consumer goods are producer goods. A “second-order” good is used to directly produce a consumer good. A branch that Crusoe uses to get a coconut from a tree is a second-order producer good. If Crusoe uses a rock with a sharp point to help him saw off a branch (a second-order good), then the rock is a third-order producer good. As so forth.

In a complex economy, there are numerous orders of producer goods — and the higher-order they are, the further removed they are from directly satisfying a consumer’s needs. Mined iron ore is a very high-order producer good indeed, far removed from directly satisfying the consumer. The oven in a bakery is a lower-order producer good, because it is closer in the production process to delivering a muffin to the customer.

We will see in future posts that this division of producer goods into lower-order and higher-order goods — the “heterogeneity of capital” — is central to understanding the Austrian perspective. It allows Austrians to make insights regarding the business cycle that are simply beyond the reach of classical economists.

More definitions: Natural resources and labor are also classified as producer goods, and capital goods are factors of production created by people.

Any action is an exchange — even without a second person — because of opportunity cost. When you act, you exchange your chance to take action a at that moment, for a chance to take action b instead.

Action also must take place in time — and action implies that the actor is uncertain about the future. If he were certain of the future, why bother acting?

Getting a bit more complex now, we round out Chapter Four with a discussion of two related concepts: 1) the law of diminishing marginal utility, and 2) the law of diminishing returns.

THE LAW OF DIMINISHING MARGINAL UTILITY

The idea that people make economic decisions “on the margin” was a key insight of economists working in the 1870s, and this concept remains central to all economics today. The idea is that, when evaluating preferences, you don’t really compare one good versus another — you compare successive units of one good to successive units of another.

You always use the first unit of a good to satisfy your most important need or desire. Successive units are devoted to less important desires. This means that successive units are not worth as much to you. This is the law of diminishing marginal utility.

For example, if you lacked running water, and had to buy bottled water for all your water needs, you might put the first bottle to use in satisfying your thirst. The second might be used to bathe yourself. The third might be used for cleaning dishes, and the fourth to give your dog water. Maybe the fifth will be stored in the garage in case the store runs out of water. That first bottle is worth more to you than the fourth or fifth.

Just as obviously, as the supply of a good increases, the marginal utility of the good decreases, and vice versa. You pay less for water than diamonds because there is plenty of water (currently) to satisfy our most critical desires, like satisfying thirst. If there were so little water that you had to pay $10,000 (more than you’d pay for a small diamond), just to get a drink and not die of thirst, you’d pay it (if you had the money).

Murphy has all kinds of interesting examples that flesh out these concepts, which is one reason that reading his book is superior to reading a blog post summary of it.

THE LAW OF DIMINISHING RETURNS

Our last concept for the chapter is probably the most complex: the law of diminishing returns. Imagine you are producing something using two scarce resources: A and B. If you fix the amount of one of these variables (A), then there is a maximum amount of output per additional unit of B. In other words, you might get more total output by adding more B, but at a certain point that output will be less per unit B, meaning that adding additional units of B may not be justified (depending on the circumstances).

I told you it’s complex. We need an example to make it concrete.

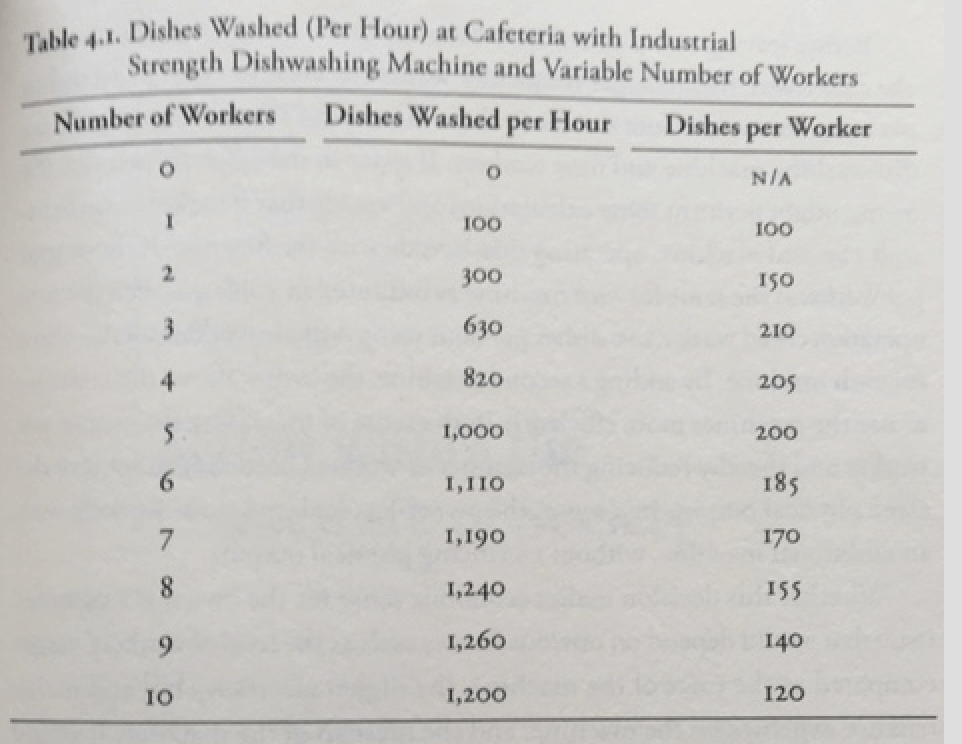

In Murphy’s example, A is an industrial strength dishwasher at a restaurant, and B is a variable number of workers using the machine. Murphy has a chart assuming one machine (A) and then showing the number of dishes washed as you add more workers (B). I’m going to take the liberty of reproducing his chart here — and I hope he’s OK with that. (If he’s not, I’ll take it down.)

As you can see, as you add workers, the number of dishes washed increases, to a point. 1 worker can wash 100 dishes. 2 can wash 300. 5 can wash 1000. The absolute number keeps going up, until you add the tenth worker, who is just in the way and actually reduces the total number of dishes washed.

But there is an upper limit to the number of dishes washed per worker: 210, achieved when there are three workers.

This is the law of diminishing returns.

Murphy notes that, during busy times, a manager may wish to employ more than three workers even though the number of dishes washed per worker goes down — simply because it may be critical to get, say, 1000 dishes washed per hour.

We are now finished with the chapters explicating the basic concepts of human action. In post 5, we will move on to action within the framework of society, and expound on the division of labor — one of the most important concepts in all of economics.

long ago, when i was young and had a future, i was w*rking in a box factory, where, among other things, we were making movie theater displays (stand up cut outs)

there were several of us on the output conveyor belt, with the appropriate brackets & glue guns to do the j*b, and, had my cow-orkers split the output, all would have been well. (i was farthest away from the machine.)

instead, they grabbed everything that came to them, leaving me with nothing to do, then, unexpectedly, when their frames were full at nearly the same time, they let everything come down the line to me.

the owner’s son, whose only qualification was his birth, came by and decided *something* had to be done, since i was standing there doing nothing, IHAO.

but, jsut as he was to intervene, the two other geniuses ran out of space, and i caught, and handled the entire machine by myself.

he went away, slightly more informed than when he showed up, but not smart enough to tell the two idiots to split the load.

it’s not how many people you assign to the j*b, it’s HOW you employ them that makes the difference.

redc1c4 (a6e73d) — 8/25/2015 @ 1:19 am“Action also must take place in time — and action implies that the actor is uncertain about the future. If he were certain of the future, why bother acting?”

Where is the uncertainty involved in turning on the tap to fill a glass of water?

Certainty about the future is not necessarily the driver as need and opportunity brought together.

Uncertainty may come in when I reach for the jug of cold water in the fridge instead of the jug of iced tea. I need fluid. Which fluid is the a or b decision.

I believe the quoted statement is a bit of an oversimplification arising from an attempt to make the model more tractable. And from it arises the old joke about the economist, engineer, and physicist each alone on his own island with a can of beans, no can opener, and a mighty hunger. Mr. Physicist grabs a stick, analyzes the can, reasons that if he hits it with a stone in the right place the can will open. Then he goes on to something else the problem having been solved. Mr. Engineer simply grabs a rock, batters the can open, and gobbles up his beans. But, Mr. Economist had it easiest of all. He simply assumed the can was open and proceeded to eat.

(In reality economists work with systems of a size and complexity few engineers are cursed to deal with. Simplifying assumptions help a little. Massive computer models still can’t seem to handle the variability human behavior (trends/fashions/etc) throw into the mix.)

{^_^}

JDow (c4e4c5) — 8/25/2015 @ 1:35 amIt is simplified. Is the simplification yours or Murphy’s, Patterico? Not that I blame you. Some people know that triangles have three sides, without knowing that for some triangles the third side is called the hypotenuse and for others the base, and the remaining two sides are simply called sides. For them, you need “One fish, two fish, red fish, blue fish”.

I could argue that the atomic bomb was a first order need for Truman, MacArthur, Nimitz, and Spaatz in WWII. And I could further argue that they made it that by their desire for Japan’s unconditional surrender.

nk (dbc370) — 8/25/2015 @ 4:01 amIt seems to me that the division of goods into “first-order”, “second-order” relies on an arbitrary definition of “consumer”, as though there is only one kind. A smelter is a consumer of metal ore and so would metal ore be a consumer good to the smelter. Sheet metal is a consumer good to an auto plant but an nth-order “producer good” to the consumer who buys a car. A computer in the 60s was a tool that no “consumer” ever encountered, and so would be some kind of nth-order producer good under this system, but nowadays “consumers” have any number of computers available to them.

I’m not seeing what making this distinction gets us. If I produce sheet metal I probably supply other producers such as auto manufacturers as well as a few “consumers”, since there are hobbyists and such who buy sheet metal. But I don’t have to DO anything different, except know what is useful to various customers, I don’t need to know how to classify my customers into 1st-order producer, 2nd-order producer, consumer, etc. Rather, I supply sheet metal in various grades, sizes, and price points.

The “law of diminishing marginal utility” doesn’t depend on classifying goods in this way. I’m interested to see where this is going.

Gabriel Hanna (13a147) — 8/25/2015 @ 6:27 amWhile I appreciate your efforts, I just bought the book to be read and savored at my leisure.

Bar Sinister (b48c12) — 8/25/2015 @ 6:46 amNo, Gabriel. Even steel workers need to eat. And their furnace is a lower order need than the ore. Read the post again.

nk (dbc370) — 8/25/2015 @ 6:56 am#4: Gabriel, I believe this ordering is based on the notion that economies serve individuals, a human-centric concept let us say. Corporations, governmental entities, and unions, although associations of humans, would not qualify.

bobathome (6f310e) — 8/25/2015 @ 7:00 am“More definitions: Natural resources and labor are also classified as producer goods”

I don’t agree you can leave that out there without response to the widely held Marxist misconception that labor is the one intrinsically different factor of production. Marxists claim that the fertility of the soil (natural resource) or the oil under it, or the potential for the dry seed on the shelf to sprout and grow when planted, all remain unchanged from yesterday through tomorrow. But the laborer’s time, if not employed today, is lost forever, while the laborer himself must still eat, rent a bed, etc.

Marx ignores that a gallon of water flowing past the water mill’s sluice down the river’s natural channel, or an hour of daylight available to the haymaking crew, or a watt of electricity unpurchased at the factory’s meter, or the heat of a furnace not smelting ore each have the same lost opportunities as the un-hired labor. There is value associated with such factors, these factors are producer goods, and labor has a value in competition with the water in the mill or the electricity in the wires so much be priced as a “good” in the same market. But introducing this change in viewpoint to a casual mind tainted by Marxism requires a bit more elaboration than the sentence provided.

Pouncer (d90bef) — 8/25/2015 @ 7:03 amPouncer,

Patience, my son. I can’t do everything in one post. Labor theory of value is addressed and exploded in post 7.

Patterico (4f098a) — 8/25/2015 @ 7:39 amThe short answer is that labor (like any good) has economic value only to the extent it satisfies a human desire.

Patterico (4f098a) — 8/25/2015 @ 7:41 amYou act as if that’s not my goal. But it is. I am very pleased to hear that.

Patterico (4f098a) — 8/25/2015 @ 7:48 am@nk:No, Gabriel. Even steel workers need to eat.

Granted, but they need to eat more than they need wireless internet or a bicycle, so does that mean wireless internet and bicycles are not consumer goods?

My need for iron ore and coke is very distant from the desire that those items satisfy, but a steel worker needs them to make steel, which is what he needs to do in order to eat. Clearly to me the n-order of iron and steel is much higher than the n-order for a steel worker, yet it’s the same good. So I’m not seeing how this first-order, second-order ranking is helping. It seems to me much simpler to regard every good as having a consumer and a producer; what do we gain by making this distinct that we can’t without it?

@bobathome:I believe this ordering is based on the notion that economies serve individuals

Okay, fine, the village blacksmith needs iron ore, and he shoes the horses and makes the plowshare for the farmer, who sells his wheat to the village general store, where the blacksmith buys his food.

Okay, so that iron ore and wheat are consumer goods for the blacksmith and plowshare and horseshoes are production goods for the blacksmith. The farmer produces wheat and consumes horseshoes and plowshares. That’s my perspective, the conventional one.

Okay, let’s look at wheat in the Mises-via-Murphy-via-Patterico persepctive. Consumer good for the blacksmith. But the horseshoes and plowshares are necessary for its production, so they are a first-order production good, but the blacksmith needs to eat wheat, which makes the wheat second-order to producing wheat, but wheat must be produced by means of horseshoes and plowshares, which makes them third-order to producing wheat…

We still run into the same problem and it doesn’t have anything to do with corporations.

Gabriel Hanna (64d4e1) — 8/25/2015 @ 7:58 amGabriel,

You make one correct observation but are confused on another point.

It makes more sense to start with the confusion. When you say: “Sheet metal is a consumer good to an auto plant” you’re treating people who are part of the production process as consumers. They are not. They are part of the production process.

I don’t want to get too bogged down as to why, for now (although I will briefly explain below). I’m simply providing definitions here, which are foundational for further arguments. I can’t make the whole argument in one post; that’s why I said there will be 17 posts.

But if you’re going to make an attempt to understand those arguments, you have to understand that for the Austrians, only true end-point consumers are “consumers.” (I’m not an economist and I have never seen this particular point discussed, but I have read enough that I am pretty confident about this statement.) While we might loosely think of a buyer for an auto plant as a “consumer” because he is buying stuff the plant needs, he isn’t. He is part of a production process. Sure, he and everyone else at the plant needs to eat. That’s why he supplies his labor for wages, and the entrepreneurs who direct the plant’s resources do that for profit. But he is not a “consumer” in the Austrian sense.

The reason why, which I can’t debate at length now, is that all producer goods derive their value from the value (which is, remember, subjective) of the consumer good they are producing. A producer good that no longer serves as part of the production process for some consumer good that someone values, itself has no value.

Which is a good place to transition to your correct observation: different goods are different things to different people. A car is a consumer good to one person, a second-order producer good to another person who uses it to transport first-order goods, and could be a third- or even fourth-order good to a different person. It all depends on how far from the satisfaction of a desire the good is, and there is nothing robotic about that. It depends on constantly changing human desires and needs.

Patterico (3cc0c1) — 8/25/2015 @ 8:11 amI don’t want to get too bogged down in angels-on-the-head-of-a-pin philosophy, but if knowing the future can cause you to change it, you don’t really know the future. Put another way, if you can change the future by acting, then you don’t really know the future. If I’m already going to have my thirst satisfied, I don’t need to drink to do it. If I need to drink to do it, then I don’t really know the future — unless my actions are all robotic and pre-determined and not coming from free will, in which case it isn’t really action in the sense Mises uses the word.

Mises’s point is true if you think about it.

On a more practical and less philosophical level, it has implications because it explains the function of entrepreneurs. A matter for another post.

Patterico (3cc0c1) — 8/25/2015 @ 8:16 amThis is right. Which is not to deny that men can associate and have common goals. But everyone acts (for Mises) as an individual. A point I maybe should have made more clear in an earlier post. But in a summary, some things fall by the wayside.

Patterico (3cc0c1) — 8/25/2015 @ 8:17 amFor them, you need “One fish, two fish, red fish, blue fish”.

Yes, nk. The need is real.

felipe (b5e0f4) — 8/25/2015 @ 8:54 amThis is similar to Fred Brooks’ book, the Mythical Man Month. Written for computer designers and such, it deals with the same problems.

Bill Cook (211b8e) — 8/25/2015 @ 10:01 am@Patterico: If a producer needs a “consumer” (in your sense) good in order to produce something, then how is that “consumer” good not a production good?

For example, iron ore. It doesn’t just appear at the head of the mine. You need tools, skills, and food to dig it out. Doesn’t that mean that the food and tools also count as production goods?

Even picking up driftwood off the beach requires an input of food. Food is a production good for the driftwood production process, is it not?

Gabriel Hanna (64d4e1) — 8/25/2015 @ 12:18 pmAny good used to produce something is a production good. If I seem to have implied otherwise somewhere, please let me know, because that would be an error and I would want to correct it.

The tools would indeed count as production goods. The food would be consumer goods that directly satisfy the needs (hunger) of the workers.

You seem to be thrown by the fact that the same goods can serve as producer goods or consumer goods; as first-order producer goods or third-order producer goods; depending on the use to which they are put by the human. But this neither invalidates the concept of heterogeneity of capital nor undercuts the theory. It just means that the world is complicated.

I don’t want to get ahead of myself, but the reason the different orders of goods are important is because of time preference. The higher-order goods are further removed in time from the ends satisfied. This has significance as you learn more.

No. Food can be a capital good — for example, we will see in post 13 that a muffin is a capital good to a baker, and a consumer good to her customer. But while you seem very pleased to recognize that human life requires some consumer goods, and that some needs are fundamental, and that therefore some consumer goods allow people to perform the function they perform in society — whether it be as a laborer, a capitalist, or an entrepreneur –nevertheless the consumer goods remain consumer goods, and they are analytically distinct from producer goods. And this is not quibbling, and there is a reason for it, which will become apparent later . . . to anyone who keeps their mind open.

Patterico (3cc0c1) — 8/25/2015 @ 9:13 pm@Patterico:You seem to be thrown by the fact that the same goods can serve as producer goods or consumer goods; as first-order producer goods or third-order producer goods…

No, I’m quite comfortable with that and have explicitly stated so more than once that consumer goods are producer goods to someone or something else. What I am not yet sure of is that it makes sense to further break them down into first, second, nth-order producer goods, and I am also not yet sure why a consumer needs to be an individual human which you seem to say Mises is saying. I am also not seeing how you can say this: “the consumer goods remain consumer goods, and they are analytically distinct from producer goods” and also this “the same goods can serve as producer goods or consumer goods”, which is a contradiction.

But this neither invalidates the concept of heterogeneity of capital nor undercuts the theory.

Fortunately I have not suggested that either of these things are true. What I am saying is that I do not see how the additional complexity adds anything to the exposition. However, you assure me that

“there is a reason for it, which will become apparent later . . . to anyone who keeps their mind open.”

And I will be delighted to learn what it is at the appropriate time.

Gabriel Hanna (64d4e1) — 8/26/2015 @ 9:58 am