This is Part 4 of my ongoing series of posts summarizing Bob Murphy’s indispensable book Choice: Cooperation, Enterprise, and Human Action . Murphy’s book is itself is a summary of Ludwig von Mises’s classic treatise “Human Action” — so you’re reading a summary of a summary . . . which sounds about right for a blog post, no?

. Murphy’s book is itself is a summary of Ludwig von Mises’s classic treatise “Human Action” — so you’re reading a summary of a summary . . . which sounds about right for a blog post, no?

The idea of this series of posts is to popularize and spread the word about Austrian economics and educate the public. I have created a category for all these posts, called “Human Action and Choice,” so that all these posts can be read (in reverse order) with a single click. Note well: any errors in these summaries are mine and not Murphy’s.

In this post, we will be defining some terms, which is an exercise that is critical to any future discussion. We will also learn a concept that separates Austrian economics from classical economics: the heterogeneity of capital. Unlike classical economists, Austrians do not view capital as one large lump. They see the capital structure as composed of different types of capital, some geared towards longer-term goals than others. As we will see later, this more accurate view of capital has staggering implications for the business cycle. Based on my reading, it seems to me that this concept is utterly foreign to classical economics, and allows Austrians to better understand the effect of changes in the monetary supply and interest rates.

In keeping with the Austrian desire to explicate universally applicable concepts, we simplify everything to a desert island, with a hypothetical Robinson Crusoe, trying to manage his environment. This sort of approach drives the Paul Krugmans of the world crazy, but it helps illustrate universal concepts that apply to any human actor.

The key insight is to classify goods as “lower-order” or “higher-order” based on how close they are in the production process to satisfying a consumer’s desire. Lower-order goods are the closest to satisfying a desire. In particular, consumer goods are goods that directly satisfy a desire. For example, Robinson Crusoe is hungry, and eats a coconut sitting on the ground. The coconut is a consumer good, or “first-order” good, because it directly satisfies Crusoe’s needs. It is the lowest-order good possible.

Goods used to produce consumer goods are producer goods. A “second-order” good is used to directly produce a consumer good. A branch that Crusoe uses to get a coconut from a tree is a second-order producer good. If Crusoe uses a rock with a sharp point to help him saw off a branch (a second-order good), then the rock is a third-order producer good. As so forth.

In a complex economy, there are numerous orders of producer goods — and the higher-order they are, the further removed they are from directly satisfying a consumer’s needs. Mined iron ore is a very high-order producer good indeed, far removed from directly satisfying the consumer. The oven in a bakery is a lower-order producer good, because it is closer in the production process to delivering a muffin to the customer.

We will see in future posts that this division of producer goods into lower-order and higher-order goods — the “heterogeneity of capital” — is central to understanding the Austrian perspective. It allows Austrians to make insights regarding the business cycle that are simply beyond the reach of classical economists.

More definitions: Natural resources and labor are also classified as producer goods, and capital goods are factors of production created by people.

Any action is an exchange — even without a second person — because of opportunity cost. When you act, you exchange your chance to take action a at that moment, for a chance to take action b instead.

Action also must take place in time — and action implies that the actor is uncertain about the future. If he were certain of the future, why bother acting?

Getting a bit more complex now, we round out Chapter Four with a discussion of two related concepts: 1) the law of diminishing marginal utility, and 2) the law of diminishing returns.

THE LAW OF DIMINISHING MARGINAL UTILITY

The idea that people make economic decisions “on the margin” was a key insight of economists working in the 1870s, and this concept remains central to all economics today. The idea is that, when evaluating preferences, you don’t really compare one good versus another — you compare successive units of one good to successive units of another.

You always use the first unit of a good to satisfy your most important need or desire. Successive units are devoted to less important desires. This means that successive units are not worth as much to you. This is the law of diminishing marginal utility.

For example, if you lacked running water, and had to buy bottled water for all your water needs, you might put the first bottle to use in satisfying your thirst. The second might be used to bathe yourself. The third might be used for cleaning dishes, and the fourth to give your dog water. Maybe the fifth will be stored in the garage in case the store runs out of water. That first bottle is worth more to you than the fourth or fifth.

Just as obviously, as the supply of a good increases, the marginal utility of the good decreases, and vice versa. You pay less for water than diamonds because there is plenty of water (currently) to satisfy our most critical desires, like satisfying thirst. If there were so little water that you had to pay $10,000 (more than you’d pay for a small diamond), just to get a drink and not die of thirst, you’d pay it (if you had the money).

Murphy has all kinds of interesting examples that flesh out these concepts, which is one reason that reading his book is superior to reading a blog post summary of it.

THE LAW OF DIMINISHING RETURNS

Our last concept for the chapter is probably the most complex: the law of diminishing returns. Imagine you are producing something using two scarce resources: A and B. If you fix the amount of one of these variables (A), then there is a maximum amount of output per additional unit of B. In other words, you might get more total output by adding more B, but at a certain point that output will be less per unit B, meaning that adding additional units of B may not be justified (depending on the circumstances).

I told you it’s complex. We need an example to make it concrete.

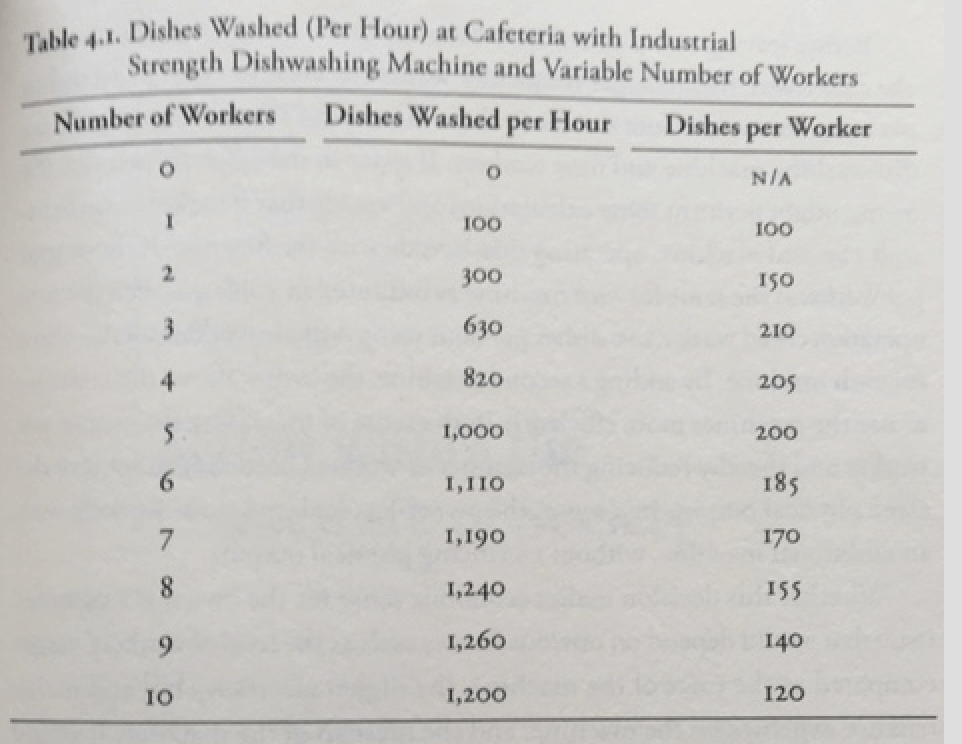

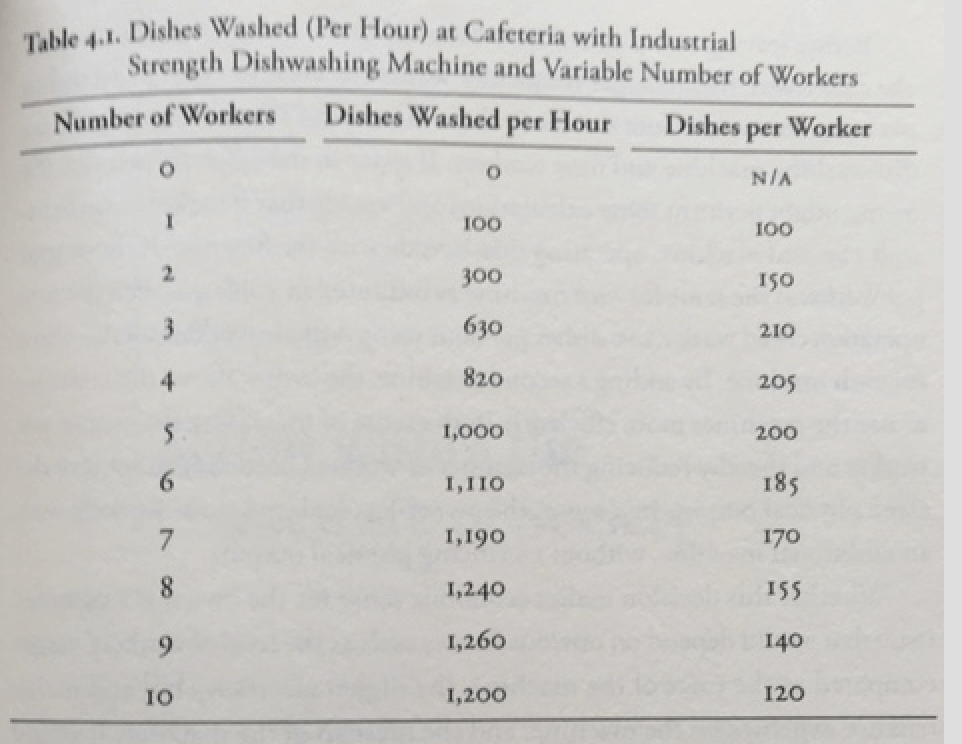

In Murphy’s example, A is an industrial strength dishwasher at a restaurant, and B is a variable number of workers using the machine. Murphy has a chart assuming one machine (A) and then showing the number of dishes washed as you add more workers (B). I’m going to take the liberty of reproducing his chart here — and I hope he’s OK with that. (If he’s not, I’ll take it down.)

As you can see, as you add workers, the number of dishes washed increases, to a point. 1 worker can wash 100 dishes. 2 can wash 300. 5 can wash 1000. The absolute number keeps going up, until you add the tenth worker, who is just in the way and actually reduces the total number of dishes washed.

But there is an upper limit to the number of dishes washed per worker: 210, achieved when there are three workers.

This is the law of diminishing returns.

Murphy notes that, during busy times, a manager may wish to employ more than three workers even though the number of dishes washed per worker goes down — simply because it may be critical to get, say, 1000 dishes washed per hour.

We are now finished with the chapters explicating the basic concepts of human action. In post 5, we will move on to action within the framework of society, and expound on the division of labor — one of the most important concepts in all of economics.