London Plane by Big Big Train: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Song

My new favorite song is “London Plane” by Big Big Train. I listen to this song once or twice a day, and have done so for several days running. I thought I would write a post about it because I have not found anything online that explores the full depth of the lyrics, and so I wanted to write something that would add to the general font of knowledge about the song.

First, have a listen, and experience the power of the voice of Big Big Train’s (sadly recently departed) lead singer David Longdon:

The place to start learning about this song is this blog post by the song’s author, Greg Spawton. I recommend his entire post to anyone interested in the song, but will quote sparingly before diving into the details. Greg explains that a “London Plane” is a type of tree that is commonly seen in London:

Like many Big Big Train songs, this one started with the title. I can’t remember where I saw or heard the phrase London Plane but it immediately struck me as an odd, and interesting, combination of words so I made a note of it and, when we came to write some new songs for the Folklore album, started to read up about the London Plane.

The London Plane is the classic city tree. It is resistant to pollution and is a common feature in the parks and streets of London and other cities. It grows to over 100 feet. It was first cross-pollinated in around 1600 and became widely planted from around 1700. It may have been discovered by the marvellously named (and spectacularly bearded) John Tradescant the Younger.

No London Plane tree has ever died of old age, so it is not known how long their natural life span is. As they re-grow vigorously when cut down, they can almost be said to be immortal.

I have written a few songs with a London theme in recent years so I began to think how a song about a tree named after the city might work. I decided that I would use a single tree as a ‘witness’ to the history of London over the last few hundred years.

Spawton decided to place his fictional London Plane tree in York Watergate next to the Thames, a place constructed in 1626. Accordingly, the historical references in the song revolve around the Thames. The song begins:

Where the road runs down

To the river bank

And the mudlarks search on the shore

Where the watermen set sail

For the towns upstream

Upon a golden course to Runnymede

The “mudlarks” referred to here are people who scavenge the muddy banks of a river, particularly the Thames. This was very common in the 1700s and 1800s, but still goes on today. In fact, an entry on Frommer’s Web site is titled Mudlarking in the Thames Might Be The Best Thing I’ve Done in London. Frommer’s travel writer actually makes scavenging in the mud at a river’s edge sound pretty interesting. You’ll have to follow the link to see the picture in which the following items are described:

Consider this image, which was taken by the north end of the Southwark Bridge. The red things aren’t rocks. They’re roof tiles, many from the medieval period, and some of which were charred by the Great Fire of 1666. The straw-like white cylinders are bits of clay pipes, which you’ll find in abundance. You will also find chunks of Tudor beer tankards, ancient bottles, smashed Delftware crockery, keys, cutlery, animal jawbones, the occasional leather shoe—anything that someone would have chucked in the river once upon a time. The Thames has mixed them all up together so you’ll find 2,500 years of history in the same field of vision.

This fellow claims that on his first mudlarking trip, he came away with “bits of 19th-century railway china, a Roman roof tile, and a grooved chunk of a medieval jug that once had a strap.” Pretty cool!

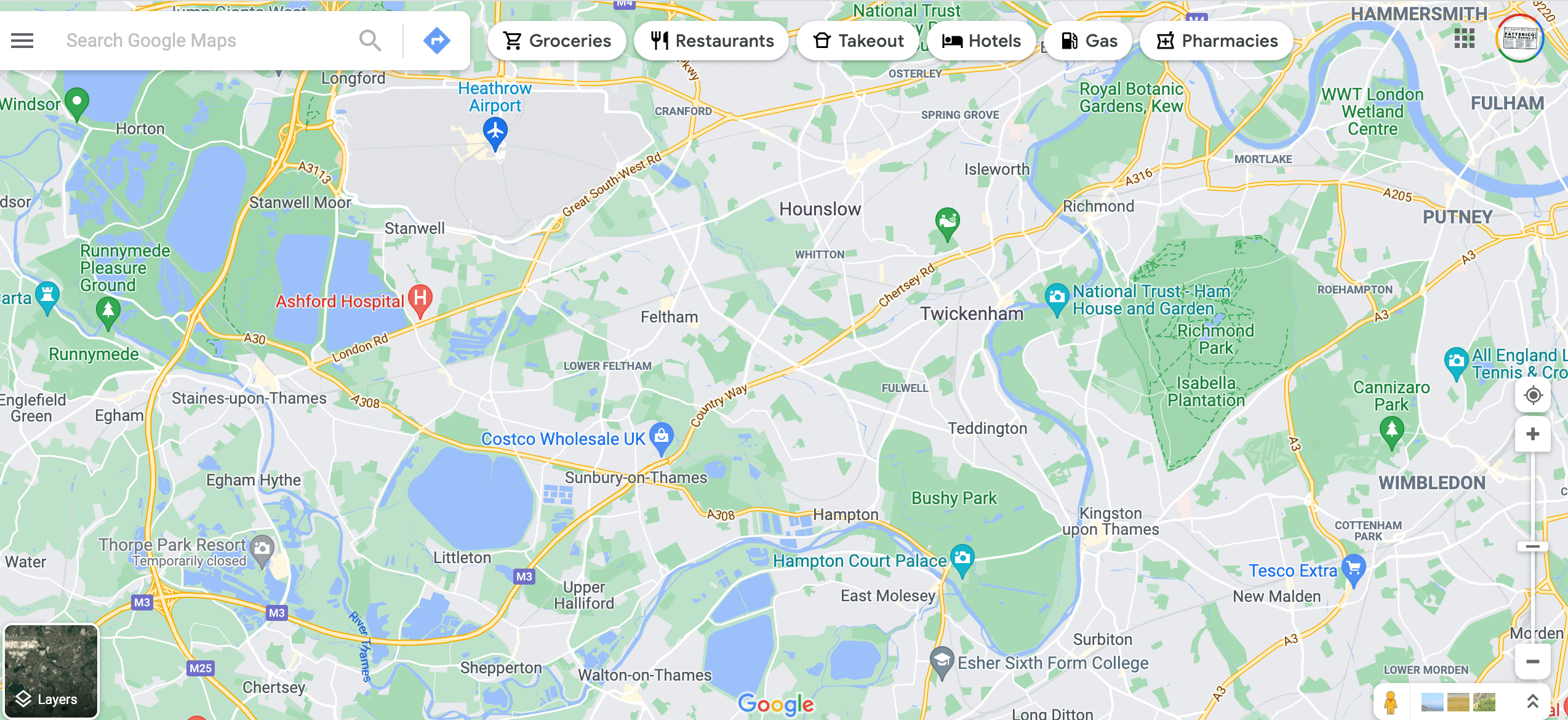

Runnymede is upstream from the Thames, to the west, as you can see in this screenshot from Google Maps:

It is, of course, famous as the most likely area where King John sealed the Magna Carta in 1215. According to the link, it’s really just a field by the Thames where people like to walk their dogs.

Where the water’s edge

Meets the squares and the streets

The river “knows the mood

Of kings and crowds and priests”

Take tea in the gardens

Drunk for a penny or two

Stars will lead you home

The line: “The river ‘knows the mood of kings and crowds and priests'” places the end of that in quotation marks so you’ll know it’s a quotation — and so it is, from Rudyard Kipling’s poem The Reeds of Runnymede. Here are the relevant lines of Kipling’s poem — which, as you will see, is an ode to the spirit of the Magna Carta sealed there at Runnymede. I have bolded the portion quoted in the song:

And still when Mob or Monarch lays

Too rude a hand on English ways,

The whisper wakes, the shudder plays,

Across the reeds at Runnymede.

And Thames, that knows the moods of kings,

And crowds and priests and suchlike things,

Rolls deep and dreadful as he brings

Their warning down from Runnymede!

Returning now to the song, we have now arrived at the chorus, with Longdon’s voice soaring like the sails of the boats on the Thames at the words “Racing on the high tides” and “Reaching for the day’s last light”:

Sailing on the English way

Racing on the high tides

Here by the riverside

Reaching for the day’s last light

Of course, the London Plane ends each day of its observation of history by reaching ever upwards, “for the day’s last light.”

When the Houses fall

And the flames meet the sky

Turner takes his boat out

To catch the light

And far downstream the Alice is clean gone

In the dark she slipped away

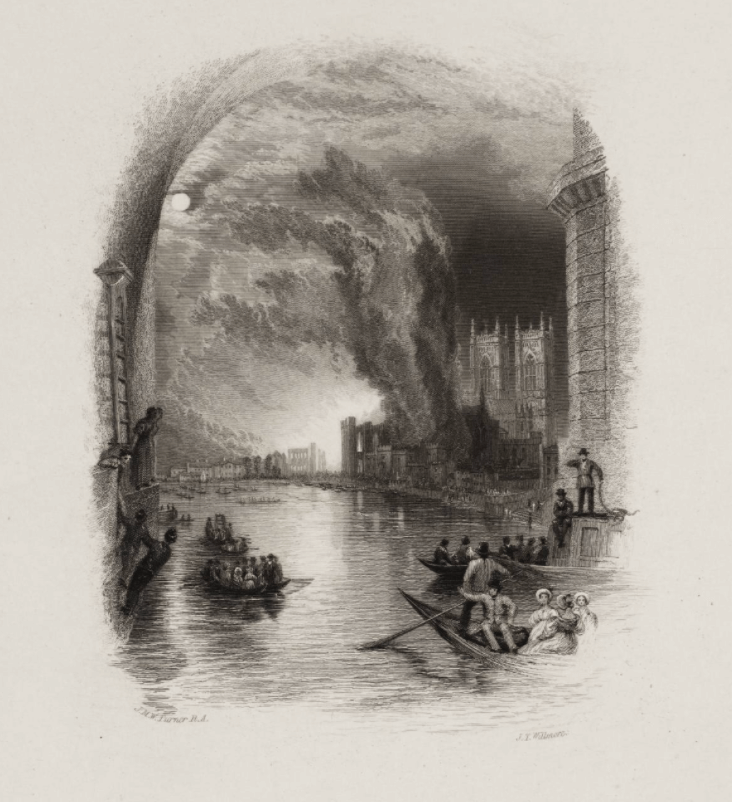

Joseph Mallord William Turner was a painter and watercolor artist who lived from 1775 to 1851. In 1834, when the Houses of Parliament caught fire, Turner rode out onto the Thames in a boat and drew what he saw:

On the night of 16 October 1834, the Houses of Parliament caught fire. Along with crowds of other astonished spectators, Turner made his way on to the river Thames in a boat to witness the spectacle of the conflagration. This vignette engraving, based on sketches taken that very night, appeared in The Keepsake, a successful ‘pocket book’ popular for its high quality illustrations and literary offerings. In this plate, the fire has entirely engulfed the Houses of Parliament although Westminster Abbey is still clearly visible beyond.

As for Alice: Bradley Birzer, in his glowing review of Folklore, the album on which “London Plane” appears, seems to believe the reference to “Alice” is an “Alice in Wonderland” reference, saying: “References to the signing of the Magna Carta as well as to Alice falling down the whole give this song something precious in its very Anglo-philia.” I like the connotation, but I think Spawton is going for something more direct: the sinking of the SS Princess Alice in the Thames in 1878. The vessel sunk near Tripcock Point, killing 650 Londoners returning from a daytrip to Kent. Bodies washed up on shore for days. Tripcock Point is “far downstream” from where the Houses of Parliament burned, and the Alice slipped away into the Thames in the darkness of evening. I’m pretty confident this is the reference Spawton intended.

After a return of the chorus with these words:

Racing on the English way

Sails against the skyline

Down by the water’s edge

Reaching for the last light

Comes a secondary chorus that comes twice in the song, which is quite lovely and showcases Longdon’s voice beautifully:

Time and tide wait for no man

A river passing by

As the crowds fade away

A mad instrumental interlude interposes itself. At times you could believe it’s Jethro Tull — Birzer says the style is straight out of Tull’s “Songs from the Wood” album, and it’s hard to disagree — except that the flute playing is less manic than Ian Anderson’s. Finally, the music slows and we get a final verse:

The fires grow cold in the east

Skylon rises in a brave new world

The clocks are stopped

And boats are held

Wikipedia describes Skylon in this way: “The Skylon was a futuristic-looking, slender, vertical, cigar-shaped steel tensegrity structure located by the Thames in London, that gave the illusion of ‘floating’ above the ground, built in 1951 for the Festival of Britain.” It wryly adds: “A popular joke of the period was that, like the British economy of 1951, ‘It had no visible means of support.'”

British Official Photograph – Museum of London website (http://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/)

Churchill scrapped Skylon in 1952, seeing the Festival and Skylon itself as representative of the previous government specifically, and socialism more generally.

As for the clocks stopping, in the original version of this post I had theorized that this was a reference to the clock on Big Ben’s famous clock tower stopping in 2005. But after I posted a link to this post on the Big Big Train Facebook page, Spawton himself clarified the reference:

Thank you for writing in such depth about the song, Patrick, most appreciated. Just one thing: the line about the clocks being stopped refers to Churchill’s funeral. If memory serves me right, the chimes of Big Ben were silenced for the day.

Unsurprisingly, Spawton’s memory is correct. This listing of the times that the chimes of Big Ben were silenced includes this entry:

1965 – the bells were silenced between 9:45am until midnight on the day of Churchill’s funeral.

Spawton also confirmed this comment from Big Big Train fan Graham Smith concerning the instrumental section and the reference to the fires growing cold in the East:

Gregory Spawton will correct me if I’m wrong but I thought the instrumental section was related to the Blitz and the line “Fires grow cold in the East” refers to London’s East End which was particularly heavily bombed.

The live show graphics also gave me that impression.

Thanks to Spawton and Smith for adding even more depth to my understanding of this song.

Time and tide wait for no man

And now the ship has sailed

And the crowds fade away

But by the water’s edge

At the end of the road

I still reach for the day’s last light

A stirring ending bringing us back to the tree reaching for the light. The singing here will send shivers down your spine.

It’s a great, great song. Give it a listen.