Politifact: the Precise Meaning of Words Doesn’t Necessarily Make Warren and Harris Wrong

[guest post by JVW]

This blog has covered various rulings that the “fact-checking” site Politifact has issued over the years. At times, we’ve been critical of rulings that we think are ill-advised, such as with the government’s mixed-messages regarding the ebola virus, or their apparent squeamishness with the dining habits of a young Barack Obama, or their reluctance to concede that Obamacare can indeed be fairly characterized as a government takeover of the healthcare system. Occasionally though, they have surprised us by, for example, reversing four years of rulings to the contrary and finally confessing that “if you like your health care plan, you can keep your plan” was in fact a lie, or the time they acknowledged that Democrat claims that Republicans would end the Medicare program were based upon a willful misrepresentation of the GOP’s platform.

Sadly, today we are back at the head-scratching obstinacy of Politifact when searching for reasons to let progressives off the hook for their wild claims. Earlier this afternoon, the site announced in a post that Tweets from prominent Democrats that allege Michael Brown was “murdered” five years ago would not be subject to an official accuracy evaluation, as the meaning of the word “murder” is — get this — “subject to some dispute.” Here is what they had to say, emphasis in this case is added by me:

After these tweets came out, PolitiFact heard from numerous readers who asked us to check whether [Sen. Kamala] Harris and [Sen. Elizabeth] Warren were correct in calling Brown’s death a “murder.”

There is no question that Wilson killed Brown, and there’s strong evidence that it was not accidental.

In discussing the case with legal experts, however, we found broad consensus that “murder” was the wrong word to use — a legal point likely familiar to Harris, a longtime prosecutor, and Warren, a law professor.

Well now, Politifact acknowledges that a whole bunch of their readers called BS on the tweets issued by those two shameless demagogues. I guess that in and of itself forced them to respond. But instead of saving time by agreeing with the legal experts with whom they consulted and concluding that the word as everyone with a modicum of sense recognizes it is not an accurate description of what transpired between Officer Darren Wilson and Michael Brown, they start dissembling:

That said, experts who have studied police-related deaths and race relations said that focusing too much on the linguistics in controversial cases comes with its own set of problems.

“I don’t know if the legalistic distinction intensifies the anger, but it does feel like an attempt to shift the debate from a discussion about the killing of black and brown people by police,” said Jean Brown, who teaches communications at Texas Christian University and specializes in media representations of African Americans. “This is unfortunate, because rather than discussing the need for de-escalation tactics and relations between police and communities of color, this has become a conversation about legal terms. Quite frankly, it’s a distraction that doesn’t help the discussion.”

Yes, what this discussion really needed is an academic from the soft sciences who specializes in racially-charged cultural studies to try and argue that using accurate language is a distraction from the goals of perfect wokeness (or should that be wokenness?).

Politifact then instructs us that murder generally means the deliberate taking of a human life, but confides to us that according to Missouri law that definition doesn’t apply to law enforcement officers acting in the line of duty! Who knew? I wonder if there are any other states that exempt police, sheriffs, and other sworn peace officers while they are on the job. They then quote a University of Missouri law professor who astounds us by reporting that law enforcement is given a pretty wide latitude in using deadly force when they feel that their lives are in danger. The things we learn from media fact-checking sites!

Our source of all of this rich legal information is forced to acknowledge that both a Missouri grand jury and a United States Department of Justice investigation concluded that Officer Wilson did not commit an act that would subject him to prosecution. Unsurprisingly, Politifact makes sure to remind us that the federal investigation detected what they believed was systemic racial bias in the Ferguson, Missouri community where this incident took place. And then, after having written a post that pretty much conclusively establishes that Senators Harris and Warren had been irresponsible in using the word “murder,” Politifact grasps at the last straw available to them in an attempt to exculpate the two Presidential aspirants:

Some legal experts argued that there’s a difference between being legally precise and using language more informally.

“When my grandmother read the newspaper, she would sometimes blurt, ‘It’s a crime!’ in response to a story,” said Ben Trachtenberg, a University of Missouri law professor. “Everyone present realized that she did not literally mean that someone described in the article had violated a criminal statute. It seems at least possible that (Harris and Warren) wished to convey a sentiment like my grandmother once did and did not intend to apply the criminal law of Missouri as one might on a law school exam.”

Finally, some cautioned that over-analyzing legal terminology can obscure the discussion of larger issues.

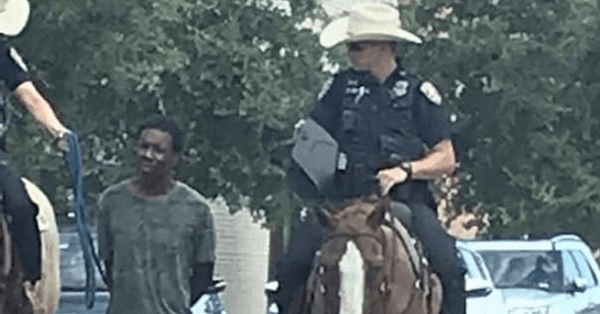

Melita M. Garza, author of the 2018 book, “They Came to Toil: Newspaper Representations of Mexicans and Immigrants in the Great Depression,” said that it’s common for people to talk past each other on matters of race and ethnicity. “That is doubly so when contemporary events have visceral past parallels whose indelible images are still rooted in our public memory,” she added.

Joy Leopold, an assistant professor of media communications at Webster University in Missouri who has studied the Brown case, said it’s not uncommon for smaller issues such as legal terminology to crop up in controversial cases like this.

“Focusing on the language opens up the opportunity for some to discredit the conversation about police brutality and the criminal justice system in general,” Leopold said.

So there you have it, helpfully distilled by the deep musings of three more academics: words, even those from famous politicians who are vying for the highest office in the land, should be taken colloquially, not literally; when speaking about race we have to understand that grievances from the past allow for narrative liberties to be taken in the present; and getting hung up on words, even when they are used irresponsibly, keeps us from achieving our perfect woke selves.

What an utter load of horse manure.

– JVW