Harry Reid Heads to His Final Sunset

[guest post by JVW]

The New York Times Magazine has an interesting profile of former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid which is dated today but I assume will be running in this Sunday’s print edition. Though I have always found the former senator to be a loathsome character, let’s right away acknowledge a fact of which I was unaware and that I don’t know has been widely reported:

Reid, who is 79, does not have long to live. I hate to be so abrupt about this, but Reid probably would not mind. In May, he went in for a colonoscopy, the results of which caused concern among his doctors. This led to an M.R.I. that turned up a lesion on Reid’s pancreas: cancer. Reid’s subdued and slightly cold manner, and aggressive anticharisma, have always made him an admirably blunt assessor of situations, including, now, his own: “As soon as you discover you have something on your pancreas, you’re dead.”

I had planned to visit Reid, who had not granted an interview since his cancer diagnosis, in November, but he put me off, saying he felt too weak. People close to him were saying that he had months left, if not weeks.

The writer, Mark Leibovich, is likely a Democrat of some or other stripe, though his other writing for the magazine doesn’t appear at first glance to be heavily partisan. He gives his subject plenty of room to criticize the President, the GOP, and Washington in general, but he also reminds his readers that Harry Reid bears a great deal of responsibility for the ill will that pervades throughout Washington these days:

Reid once called the Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan a “political hack,” Justice Clarence Thomas “an embarrassment” and President George W. Bush a “loser” (for which he later apologized) and a “liar” (for which he did not). In 2016, he dismissed Trump as “a big fat guy” who “didn’t win many fights.” Reid himself was more than ready to fight, and fight dirty: “I was always willing to do things that others were not willing to do,” he told me.

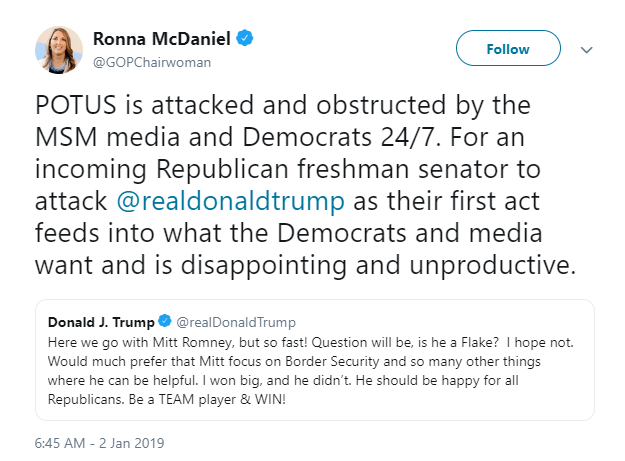

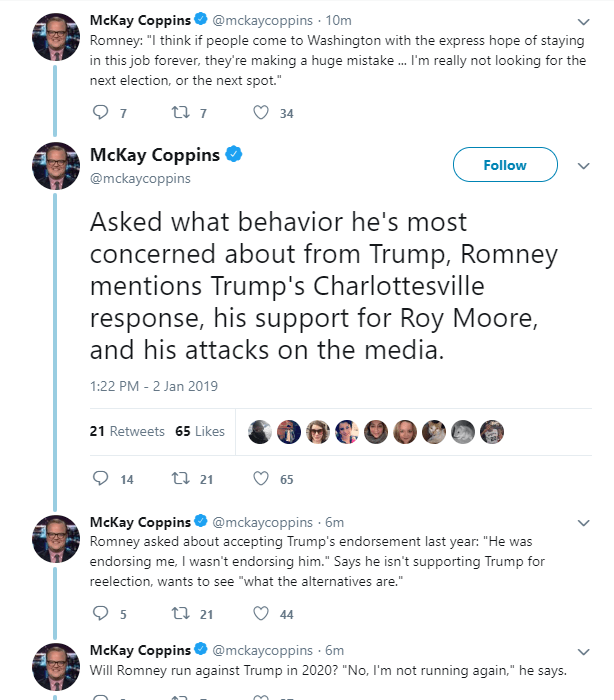

During the 2012 presidential campaign, he claimed, with no proof, that Mitt Romney had not paid any taxes over the past decade. Romney released tax returns showing that he did. After the election, Reid told CNN by way of self-justification, “Romney didn’t win, did he?” Reid took rightful criticism over this.

[. . .]

In some ways, Washington, under Trump, has devolved into the feral state that Reid, in his misanthropic heart, always knew it could become under the right conditions.

Misanthropic, needy, and vain are some of the characteristics of Reid that come across in this profile. Though the future senator grew up in a broken home in a town that supposedly contained “at least a half-dozen brothels and not a single church” (this might be the kind of hokum and bunkum that someone like Harry Reid passes along to a NYT Magazine profiler), he now lives in what Leibovich calls “a McMansion in a gated community outside of Las Vegas,” and the former senator has round-the-clock security protecting him. Always bumbling and clumsy where issues of diversity are concerned, the host makes a big deal of showing his guest a menorah that he has brought out for Hanukkah, even though the reporter describes himself as having only nominal Jewish identity. In an era where intersectionality is now the organizing principle of the left, we aren’t likely to see a Harry Reid type in this kind of leadership role anytime soon.

It can’t be easy to have to come to grips with your legacy on your deathbed. Reid admits that he still follows the Washington scene pretty closely. He takes pride in his role in passing Obamacare, and he defends curtailing the filibuster for judicial appointments pointing out that it helped confirm 100 judges appointed by President Obama, even if it did allow Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh to win confirmation to the Supreme Court. He speaks with his successor, Chuck Schumer, from time to time though it sounds as if Schumer is not particularly interested in any advice that Reid has to offer, and he maintains contact with old friends Nancy Pelosi and Dick Durbin. But Reid’s essential weirdness continues to be a hallmark of his character. He tells Leibovich a sappy and almost certainly untrue story of his last conversation with John McCain, which even the mostly respectful reporter finds highly unbelievable:

Reading Reid can be difficult. Is he playing a game or working an angle or even laughing at a private joke he just told himself? When speaking of his final goodbye with McCain, he broke into a strange little grin, his lips pressed upward as if he could have been stifling either amusement or tears. It occurred to me that Reid, typically as self-aware as he is unsentimental, could have been engaged in a gentle playacting of how two old Senate combatants of a fast-vanishing era are supposed to say goodbye to each other for posterity.

Harry Reid’s legacy is uniformly negative. He pursued political power relentlessly and showed no scruples about impugning the character and motives of men and women far more worthy than he as he scrapped his way through Washington. He’s one of those “public servants” who arrived in our nation’s capital as a man of moderate wealth, yet left 35 years later having increased his holdings by at least tenfold and possibly as much as fifteen times their original worth, all while keeping two households (Nevada and Washington) on a Senator’s salary which topped out at $194,000 and with a wife whom I don’t believe ever worked outside the Reid home. We can wish him smooth passage to his eternal reward yet still recognize that Senator Tom Cotton’s assessment of him is just as trenchant today as it was when it was delivered two-and-one-half years ago.

– JVW